By Harley Shaw.

Leaving the Rio Grande and crossing the south end of the Black Range isn’t easy, even today. In a modern sedan, you have only one shot—State Highway 152 over so-called Emory Pass. As noted in an earlier article in this newsletter, even Emory didn’t go that way, nor did hardly anyone else until 1935, when motorized earth moving equipment pushed a two-lane dirt road over, connecting Hot Springs with Silver City via Hillsboro and Kingston. Before that, most wheeled vehicles—wagons, stagecoaches, and early autos–went around the south end of Cooke’s Peak, as did the railroad. And today, in spite of the well-maintained paved road through the pass, most folks choose to go around the south end of the mountain when weather is bad. In a modern car on pavement, this might add a half hour to the trip from Hot Springs (T or C) to Silver City, so nobody complains.

Prior to World War One, horseback or foot travelers had limited options, unless they lived and worked on the mountain. No doubt, the Apaches knew faint trails that crossed in many places, but the Apaches were, in themselves, a factor that made travelers choosy about routes. Thick brush and deep canyons were great ambush sites. Known and usable thoroughfares were no more abundant than they are today, and passing from the Rio Grande to the Mimbres was probably a multi-day endeavor, regardless of the route you chose. The big factor, one we forget nowadays, was water. Horses and humans needed to drink, and you couldn’t carry enough along to quench a pack string or a company of troops, much less both. Once you left the Rio Grande, your route was constrained by the location of springs, preferably big ones, which were scarce in the Southwest. Today, I-25 zaps south criss-crossing the Rio Grande, State Highway 26 connects Hatch and Deming at 65 mph, so looping south around the mountain is no big deal. I-10 makes a fairly straight shot across seemingly flat desert from El Paso to Deming to Tucson, but trying such a route back then, even in the winter, courted death for livestock and men. And what now feels flat in a 300 horsepower vehicle was laborious and tedious afoot or horseback, crossing hundreds of sandy desert washes and ridges.

Historians studying the pre-1900 trails describe two early routes from the Rio Grande through New Mexico Territory (which then included Arizona) to California: the South Trail; and The Gila Cutoff. Anyone headed south from Santa Fe or Albuquerque had two approaches to the South Trail: they could leave the Rio Grande at Paraje, some 50 miles south of Socorro and make the risky crossing of the Jornada del Muerto to Rincon, then turn west; or they could continue down the river, struggling with canyons, crossings, and quick sand, to a point near current day Hatch, then swing SW to Cooke’s Spring to join the old trail from El Paso. The river route was impassable for wagons, making the Jornada the only practicable wagon road. But it involved a loop to the east that added at least two days travel before travelers by wagon could turn west.

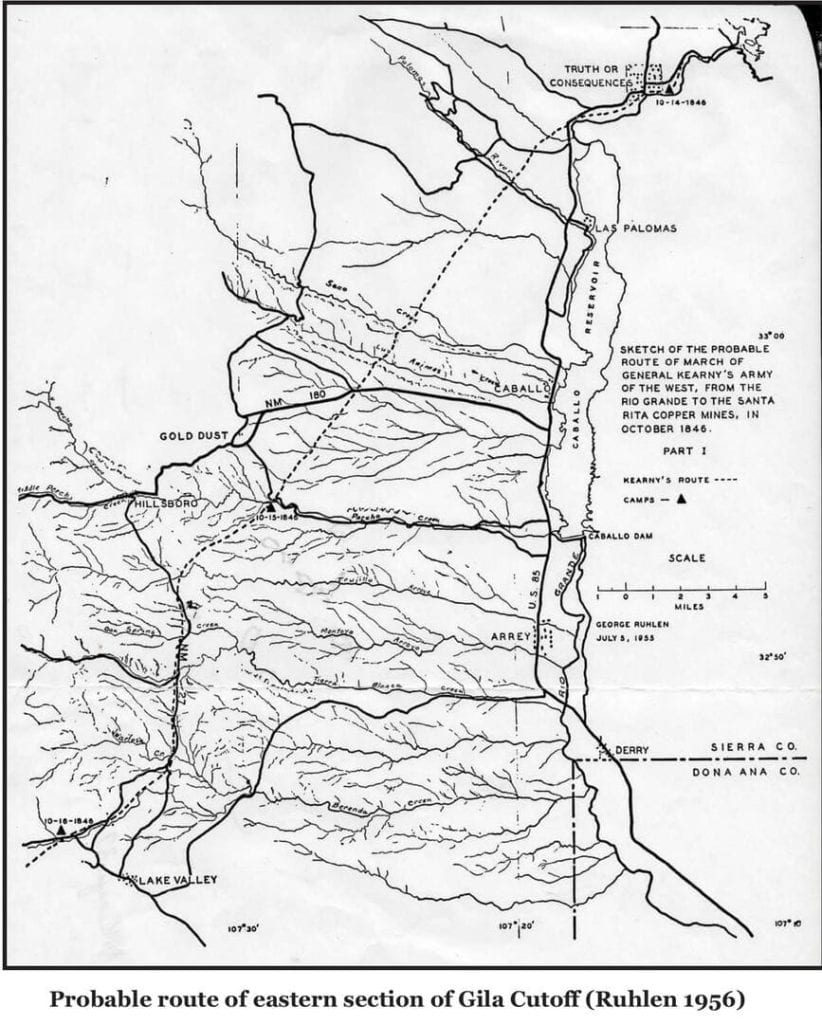

Horseback or Shank’s mare travelers, could take the rougher and obscure Gila Cutoff. Those coming from the north could leave the Rio Grande near the present-day site of Truth or Consequences and pass southwest across the lower reaches of Palomas, Seco, Animas, and Percha Creeks. They would hit Berrenda Creek in the vicinity of the point Highway 27 now crosses it and turn up that creek for several miles, leaving it before entering the steeper slopes of the mountain, crossing Macho Creek and passing up Pollock Creek to cross the low pass near the head of a tributary of Gavilan. From that point, they passed the Copper Mines and headed down the Gila River. This route was probably used by the early Mimbrenos, by Spanish troops riding from Janos in search of Apaches, and by Fremont, Kearny and Emory, and Goulding. Of these, Goulding noted that it had the appearance of an ancient and well-worn trail. For early Anglos headed to California, it by-passed Tucson and went straight to the villages of the friendly Pima Indians. From there, it joined the South Trail, following the lower Gila River to the Colorado. The leg of the Gila Cutoff that crossed the Black Range also gave horsemen coming from the north a shorter option to reach the South Trail; they needed only to turn southwest when they hit the Mimbres and catch the trail, probably near present day Lordsburg. The Gila Cutoff, throughout most of its length, was too rough for wheeled vehicles.

As early as 1900, official highway maps were showing another route across the crest of the Black Range. This one followed the main tributary of Berrenda Creek to the summit, then descended past the Monarch Mine, later to be known as the Royal John Mine. The history of this road is unclear and worthy of additional research. On the 1900 State Highway Engineer’s map, it appears in red, seemingly overlaying the actual printed map and possibly having been added at some later time. The legend calls it a federally funded highway! On our digitized copy of the State Engineer’s map for 1912, the road is missing. By 1918, the road is again marked in red and classed as federally funded. By 1920, it is printed in black and classed as an ungraded earth highway. On the 1923, it shows as an improved road, although the various classes are difficult to distinguish. By 1927, it has disappeared from the map and the beginnings of pushing a highway through Emory Pass to Kingston and Hillsboro show instead. The road is also missing on the 1930 map, and the progress of the push toward Emory Pass again shown. In all the literature we’ve read, we find no definite story of anyone crossing it. Hillsboro resident Lonnie Rubio says his father remembered the road and that the two of them tried to drive it with an ATV in 1973. By then it was so washed out and grown over that they couldn’t follow it up Berrenda Creek and across the summit. Lonnie’s father also told him that when he hauled a wagon load of produce from Caballo to the Mimbres Valley, he headed southwest and picked up a wagon road that went south of the Black Range. This was probably the Butterfield Trail that passed by Cooke’s Spring.

Shortly after World War I, two developments apparently led boosters to dream of a third route across the south Black Range. First, Elephant Butte and Roosevelt Dams had been completed. Such engineering feats are taken for granted in our times, but they were marvels of accomplishment in 1920. Second, by 1920, the automobile was becoming reliable enough for more adventurous souls to indulge a new hobby—touring. The Indians had been subdued for 30 years and the auto rendered travel available to individuals, independent of railroads or without the need of horses. With a can of extra gas and a couple jugs of water auto routes increased the daily range of travelers and allowed direct routes between towns, independent of springs. Boosters in places like Hot Springs and Silver City saw an opportunity to attract new dollars.

We don’t know who proposed the idea or came up with the phrase, but for a short time around 1921, the concept of a Dam to Dam Highway—a tourist route between Elephant Butte Dam in New Mexico and Roosevelt Dam in Arizona caught on.

The idea advanced to the point that a large highway dedication ceremony happened somewhere on Berrenda Creek on July 4, 1921, we’re not sure where, but a panoramic photo of the gathering exists. The planned route, insofar as we’ve determined, ran southwest out of Hot Springs, probably more or less following the old Gila Cutoff route across Palomas, Seco, and Animas Creeks. It diverted westward to Hillsboro, which was then in its heyday as the Sierra County Seat; and businessmen in Hillsboro were almost certainly among the main proponents of the route. An overnighter in Hillsboro and stocking up on gas, water, and food was potentially in the travelers’ plans. The highway then headed south, more or less along the route of current Highway 27. At this point the route, and its purpose, become uncertain, even confusing. For some time, in researching the highway, I had assumed it probably followed the old Gila Cutoff across the Black Range. However, the roughness of this route made it no more suitable for automobiles, perhaps even less so, than it had been for wagons. It was a horse trail. The road went elsewhere. An early State Highway Engineer’s report noted that the route might go by way of Mule Springs. Mule Springs lies near the first low saddle north of Cooke’s Peak, near the old mining townsite of Cooke. Why this route was promoted, rather than the better-known Butterfield trail through Cooke’s Spring is unknown. Another option was certainly the rough road up Berrenda Creek down the west side through Camp Monarch, ergo over what is now the Royal John Mine road. Perhaps both the Berrenda and Mule Springs routes were considered.

Both routes spurned Deming, which would have seemed a natural place for a stopover. They did cut some miles off of the road distance between Elephant Butte and Silver City, and certainly passed fine scenery and at least one point of interest in the form of the ghost town of Cooke, but both had to be rougher than the road around the south end of the range might have been. A lot of room for research remains.

Stories vary regarding why the idea died. One says that a serious thunderstorm eradicated the road through the pass at Mule Springs or the Berrenda Road, or both, shortly after the dedication, so it was never used. Another thought is that the average driver decided that the route around the south end of the mountain, perhaps with a stop in Deming made more sense, so the route just faded from misuse. Whatever the case, the idea of the Dam to Dam Highway apparently didn’t take. If races or other such booster events were planned, we’ve found no record so far of their happening. Seemingly, the idea was just a splash that didn’t catch the tourist’s fancy. The concept faded. By 1927, road builders were headed for Emory Pass. If the Dam to Dam moniker was ever applied to this newer route, we’ve yet to find it in print.

But the Dam to Dam highway became real, if unnamed. With a minor, and much more sensational, exception, the route as planned exists today, though nobody that I know specifically plans a Dam to Dam drive. The big change in the original route is present Highway 152 through Hillsboro and Kingston and across the Black Range to the Copper Mines and Silver City. Pushing a road over Emory Pass was probably beyond anyone’s comprehension in 1921, but became feasible by 1934. Considering that only 13 years had passed, perhaps the ghost of Dam to Dam nudged the construction of this route—infinitely more scenic than the rough road by way of Mule Spring.

Whatever the case, once travelers heading into Silver City pass the junction of Highways 152 and 61, they are on the original Dam to Dam route. In concept, it crossed the Gila River and headed north to Mule Creek Pass, thence past Clifton, to Safford, across the San Carlos Reservation, turning northerly at Globe and down the long hill to the Salt River and Roosevelt Dam.

Roosevelt Dam has been heightened since its original construction, and a striking new bridge crosses the lake just above the dam, replacing the old narrow passageway that crossed the dam itself. Patty and I drive parts of the Dam to Dam highway on most of our trips to see family, either in Chino Valley to the north or to the town of Oracle. We prefer its scenery and lack of traffic to the flat terrain crossed by I-10 and the heavy traffic of Tucson and Phoenix.

I spent a chunk of my career working near Roosevelt Dam and frequently drove back and forth across the old highway crossing Roosevelt Dam. For various reasons, I’ve driven segments of that old “Dam to Dam” highway much of my life, oblivious to the dreams of those early boosters.

So…then…well…I’ll be damned!